Towns and Cities

11 min readMulture and environment change continuously. The rate of change varies/widely, however, and nowhere is it more dramatically visible than in the cities and towns of China. Even in the hinterland that is northwest Yunnan, the seats of government administration for prefectures, counties, andtownships have grown enormously as compared with the modest changes seen in villages.

The opposite is true of cities and towns; during most of the last 60 years, the spectacular expansion of urban infrastructure and population was mostly due to an increase in the size of government and government enterprises.More recently, private investment for economic development has increased dramatically in urban centers near tourism, mineral, and hydropower resources.

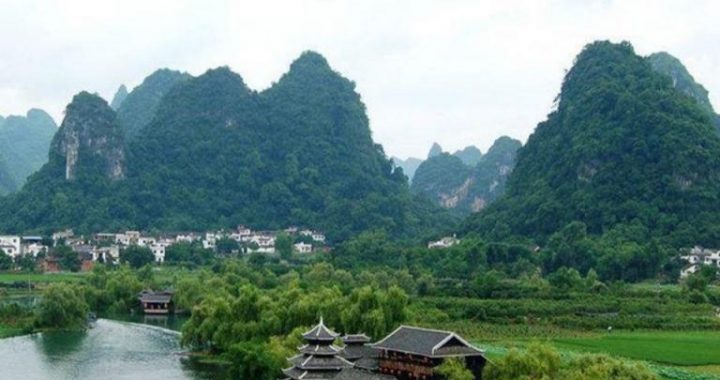

This development pattern is not unique to China. Other repeatphotography projects in Asia and South America have documented similar trends in the differential rates of change between villages and cities. From a global context, demographers tell us that in 2007, the world’s human population became more urban than rural for the first time ever. In the developing world, it is estimated that five million people are moving to cities from the countryside each month. Essentially, we can witness this rural-to-Three urban centers are highlighted here: the prefectural centers ofLijiang and Zhongdian and the county town of Deqin. All three happen to share a similar story of development. To varying degrees, all had been local government and economic hubs for centuries.

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, however, the cities expanded as increasingly important government centers. Beginning in the 1970s, theireconomies also expanded to include state-run enterprises that exploited the rich natural resources of the region, especially timber from surrounding forests. As timber harvest declined and was eventually banned in 1998, the central government began allowing these cities to become tourist centers. All three are now on the forefront of Chinai’s burgeoning tourism industry.Although Zhongdian accomplished a major tourism-marketing coup by becoming officially recognized as Shangri-La, Lijiang’s story is even more impressive. Its rise from a remote mountain town to a world-class tourist destination has been meteoric. The tourism pathway of development was laid initially in 1986, when the central government officially recognized Lijiang Ancient Town as a famous historical and cultural city in China. It was then sanctioned for international tourism by the central government in 1990, a year when it had 160,000 visitors.

Three major breakthroughs happened in the following decade. Yulong Snow Mountain,a few kilometers north of Lijiang, was designated as a national-level tourist attraction in 1992. An airport opened in 1995, cutting travel time between the provincial capital of Kunming and Lijiang from a 10-hour bus ride to a 30-minute flight.Finally, after three years of concerted effort by Lijiang officials, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)added Lijiang Ancient Town to the prestigious list of cultural World Heritage sites in 1997. All these events, combined with a rapidly expanding Chinesemiddle class, resulted in more than 4.2 million tourist visits by 2008, an astonishing increase of 2,500 percent in two decades.Tourism is certainly the big economic story in northwest Yunnan, but it is not the only one.

The central government is making huge infrastructure investments that are fueling growth in cities and towns throughout theregion.Beyond funding local improvements, the Initiative is also developinghydropower and mineral resources for export.I would like you to consider one final point when viewing these photographs. Repeat photography documents only visible signs of change: urban sprawl across farmland, new buildings replacing old ones, and electric power plants being built in what were remote valleys. Largely unseen in repeated images are major changes taking place in local cultures, such as migration of youths from villages to urban centers with the resulting loss of traditional knowledge systems and local language skills or the changein ownership of Lijiang buildings from local residences to tourist shops owned by outsiders. These cultural shifts may not be captured by repeat photography, but they are changing as fast as the visible indicators.The next five sets of photographs illustrate an extraordinary century of change in Lijiang city. Within the past 15 years, Lijiang has become a world-class tourist destination.

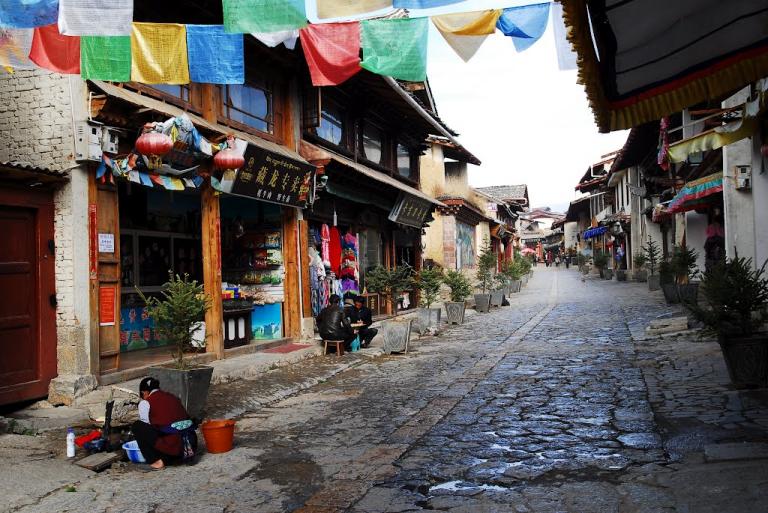

One of the most popular attractions in China, Lijiang has the perfect mix of appealing elements:a beautifully quaint”ancient town”nestled in majestic mountain scenery with a colorful Naxi minority population.Visible on the lower slopes of surroundinghills are some modern buildings adjacent to the old town, but they do notdominate this view. Below the tranquil sea of roofs, however, lies enormous cultural change. Most of the original buildings have been converted from local Naxi households to shops, restaurants, and lodging catering to tourists, most owned by non-Naxi outsiders. All of the four million tourists that visit Lijiang each year will take a stroll through the cobblestone alleyways of Ancient Town.Compare the last set of photos of Lijiang Ancient Town with this set of the new town. Taken from almost the same location near the top of Lion Hill, Ancient Town lies to the east and appears more or less unchanged.Looking north over the new town toward Yulong Snow Mountain is where the big changes can be seen. Here is the most visible evidence of Lijiang’s recent urban expansion to accommodate astronomical tourism growth.

On his expedition to Tiger Leaping Gorge,C.P. FitzGerald stopped in Lijiang and took this photograph of a double-arched, stone bridge spanning the main canal in the heart of the old town. His image captures a group of Tibetans who were part of a trading caravan from Lhasa, following a tradition that is centuries old. Today, millions of tourists from all over China and the world travel to Lijiang, crossing and often photographing the same picturesque bridge.Lijiang has been a destination for travelers from distant regions for centuries. In previous times visitors were mostly Tibetan traders from the west, and now they’ re mostly Han tourists from eastern China. Lijiang has also been busy with foreigners for the last 150 years. Edward Amundsen, a Norwegian missionary, traveled from Sichuan south to Yunnan in the winter of 1898-1899. In his travel log published a year later, he leaves out a description of Lijiang because it is”too well known(to Westerners) for me to say anything about…”He is referring to less than a dozen European travelers who had already come through Lijiang and documented their visits.

Travelers have visited and written about Lijiang ever since.Peter Goullart photographed the house and office that he used as a representative of the Chinese Industrial Cooperatives,a government agency at the time. This building is not in the ancient part of Lijiang.A short walk over the hill brings you to his neighborhood in what was then the adjacent village of Wuto on the northwest slope of Lion Hill. It is surprisingly easy tofind. People in the area still know it as the “Russian’s”house. Goullart’s book, Forgotten Kingdom, is by far the best ever written in English about old-time Lijiang and Naxi life.Although Goullart’s house is almost the same today as in the 1940s, everything else around it has changed. The neighboring houses have all been replaced with new structures and the distant farmland on the plain has been replaced with Lijiang’s new urban expansion. The tower visible in the distance is Lijiang’s first five-star hotel, complete with a rotating restaurant on the top floor.There are two family names used by most Naxi people, Mu and He. Mu is exclusive to Naxi royalty and their descendants, while nearly everybody else is named He. The gate pictured here stands in front of the original residence of the Naxi chiefs at the southern outskirts of Lijiang Ancient Town. It is actually a memorial given to a Mu chieftain in 1620 by the Ming emperor. The two large horizontal characters above the door mean “loyalty and righteousness,”while the smaller vertical characters in the upper panel proclaim this to be by”Imperial decree.”Similar to FitzGerald’s photograph of the famous stone bridge, Rock’ sphotograph of the Mu Gate captures another picturesque attraction of Lijiang Ancient Town that today is visited and photographed by millions of tourists.

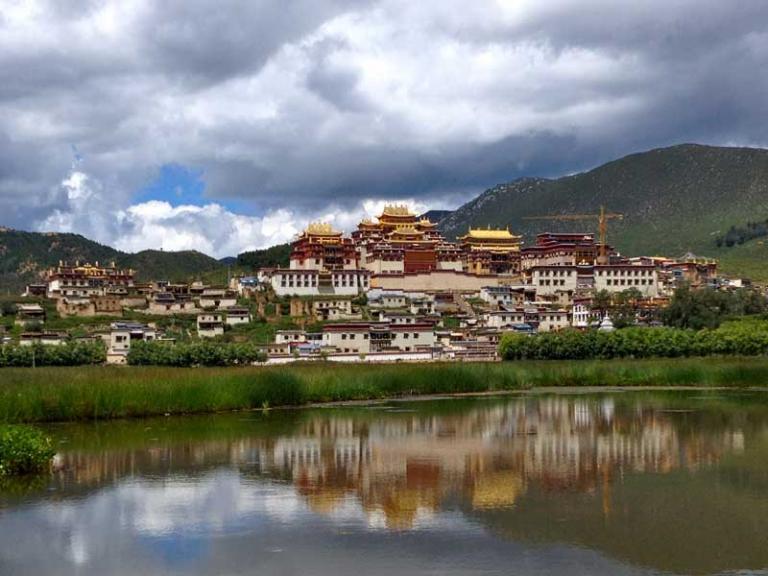

Unlike the stone bridge, however, the gate photographed by Rock was destroyed some time ago and rebuilt in the late 1990s in a style that closely resembles the original.Shigu was on the main path of the Yunnan Tea and Horse Road, visible in the foreground of the 1923 photograph, and was a common stage stop for travelers along the route. Consisting of about 200 houses in the 1920s, it wasalso an important market town for the valley. It remains a local economic and government hub now as the administrative headquarters of Shigu Township.Shigu also lies at the apex of the First Bend of the Yangtze River, where itreverses course from south to north. If the river went straight and followed an ancient river path south, it would join the Red River and empty intothe Pacific Ocean near Haiphong, Viet Nam. Instead it traverses another2,000 kilometers (1,200 miles) through the heart of China and has become its major river. Therefore, the First Bend is famous in Chinese mythology.Redirecting the river flow is attributed to Yu the Great, founder of theXia Dynasty four thousand years ago and China’s first hydroengineer. Not surprisingly, the First Bend is a major attraction on the Lijiang tourist circuit.With thousands of busloads of tourists passing by what is otherwise a remote location, China Mobile pronounces in this billboard that it “can put you in toucb with your family-anytime, anywbere.”Zhongdian is the county seat of what was called Zhongdian County until 2001, when the official name was changed to Shangri-La. The name change was a wildly successful tourism marketing tactic. Although not the same astronomical growth as in Lijiang, tourism has nevertheless increasedsignificantly since the airport opened in 1999. The city’s Tibetan name is Gyalthang, although the use of the Chinese name Zhongdian dates back many centuries as the district seat north of the Jinsha River in the point of the First Bend. Interestingly, among Western explorers, Zhongdian was a remote place not on any of the main Yunnan Tea and Horse Road paths. Few visited Zhongdian and even fewer photographed it.Frank Kingdon-Ward took this rare Zhongdian photograph from the west slope of Big Turtle Mountain overlooking “a corner of Chung-tien,”a hamlet of about 300 houses at the time. Before roads were built in the 1950s, the narrow main street of Zhongdian ran in front of the houses in the immediate foreground. There were many hotels and restaurants along the road, and it is likely that Kingdon-Ward resided nearby.

Shockingly, and similar to Lijiang Ancient Town, little of the vast change that has taken place in Zhongdian during the past century is visible in this photograph. But as in Lijiang, ifyou turn less than 90 degrees to the right(north), the view is dramatically different.The county seat of Deqin is tucked into the head of this remote valley, nearly two weeks of travel time north of Lijiang in Joseph Rock’s day.Nevertheless, it was an important trading outpost along the Yunnan Tea and Horse Road, the last in Yunnan before the Tibetan frontier. The frontier location left Deqin open to repeated attacks by Tibetan brigands from thenorth, and many merchants stockpiled their most valuable goods in villages two or three days south along the Lancang River.Although still remote by modern standards, Deqin today is now linked with the outside world by the recently paved National Highway 214, seen traversing slopes on both sides of the valley, as well as by all modern communications technology, including a fiber optic cable. The 2003photograph illustrates how modern Deqin has expanded down valley from its almost invisible presence in the 1923 image, gobbling up the terraced barley fields of old. Until 2000, most of this growth was from government expansion fueled by state-run logging operations. Logging was banned in1998, and tourism now prevails as the economic pillar of Deqin.Joseph Rock captioned this photograph”the bleak town”of Deqin, situated “at the bead of a bleak valley.”At more than 3,300 meters(11,000feet) in elevation, it certainly can be a cold and dusty place during the winter months. Rock must have had a particularly bad couple of weeks based here. In my two years of living in Deqin,I found the clear, high-altitude skies of winter to be stunningly blue and the sun at this low latitude to be penetratingly warm. The problem is that Deqin lies in a deep valley surrounded by 4,500-meter(nearly 15,000-foot) ridges, so the mid-winter sun hits the town for only a short time.

The old town of Deqin no longer exists in the same sense as Lijiang Ancient Town or even the old part of Zhongdian that remains. The modern scene is dominated by an ugly institutional-style building commonly built in towns across China during the 1980s and 1990s. Remaining within the newer structures, however, are a few old household compounds, often upgraded somewhat, that still contain livestock.A few yaks and many black Tibetan pigs (seen in the lower right of the 1923 photo) are still residents of downtown Deqin.Then, as now, Deqin was the trading hub of the region. It consisted of300 to 400 houses that filled the valley wall to wall and was inhabited by Tibetan, Naxi, and Han. The primarily Han merchants traded with Tibetans from all over the southeastern Tibetan Plateau and even from the mountains of northern Burma. They brought in musk, skins, gold dust, and medicines.As recounted by Thomas Thornville Cooper after his 1868 visit, Deqin: eld considerable importance as a mart to which the Tibetans brought large quantities of musk, whicb they exchanged for a very fine description of black tea, sugar, snuff and tobacco, all products that are produced in abundance farther south in Yunnan.”Musk was by far the most valuable product traded in Deqin. Obtained from any of seven species of musk deer(genus Moschus), the gland or “musk pod”is removed and dried. The resulting “musk grain”has been used since ancient times as a medicine and as a fixative to make perfume scent long lasting. It has long been one of the most expensive natural products in the world.A Frenchman named Gaston Peronne was a musk trader who lived in Deqin from 1903 through at least the 1920s, supplying the French perfume industry. All musk deer are now endangered with extinction due to heavy harvest for musk. Although global trade is controlled under an international treaty and hunting is banned in China, musk deer are still heavily and illegally harvested for their gland.A synthetic compound has been developed to replace musk in perfume production, but it is still widely used in as many as 400 traditional Asian medicines.There are serious environmental consequences to the new development taking place in cities and towns across northwest Yunnan. Nearly all this development is spurred, at least in part, by government investment.

Even popular tourist sites got their start through heavy government investment in infrastructure, but all county and township headquarters across the region are experiencing growth. The photographs here show the construction of a new hydroelectric facility to supply the county seat of Yunlong County,a relatively remote place not on any tourist itinerary. Starting in the distance up-valley,a diversion canal was being constructed on the left side of the valley in 2004, with debris being dumped directly into the Pi River along theseveral kilometers of its length. The canal enters a short tunnel at the veryleft edge of the new photograph before dropping into the electric generating plant.