The Artistic Process in Performance

4 min readIn 1935, the great Chinese opera star Mei Lanfang (1894-1961 AD) toured the former Soviet Union.

Some fans returned to see him perform the Kunqu opera Ci Hu (Killing the Tiger General) time after time. Noticing that his movements differed with each performance, they demanded to know the reason.A prominent Soviet dramatist offered the following explanation: Traditional Chinese opera is characterized by both its discipline and its freedom. While adhering to a set of artistic rules and staging requirements, it also allows improvised action. This interplay between control and spontaneity repre-sents the essence of Kunqu opera. Kunqu performances offer many examples of this process. It is espe-cially apparent in the work of several great Kunqu artists of the Ming-Qing period.

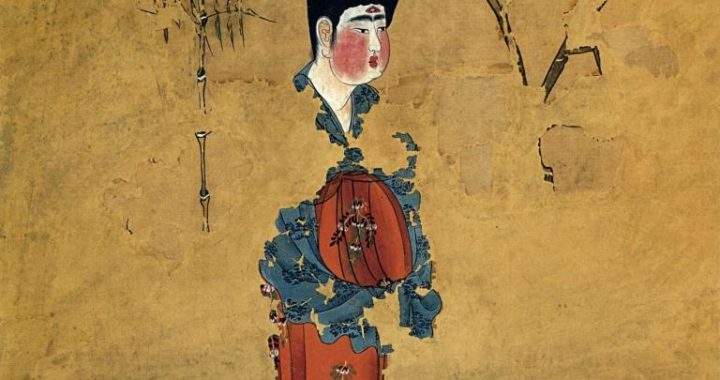

Kunqu opera Xiao Fang Niu(The Little Cowherd), performance still During the Tianqi(1621-1627 AD) and Chongzhen(1628-1644 AD) reign periods of the Ming Dynasty, two Kunqu troupes, the Xinghua troupe and the Hualin troupe, simultaneously staged productions of the opera Mingfeng Ji(Legend of the Phoenix) in Nanjing.A member of the Hualin troupe surnamed Li,and a member of the Xinghua troupe surnamed Ma, both played the part of the treacherous ministerYan Song(1480-1567 AD). Li’s performance was widely acclaimed to be much better than that of Ma.

Ma was so mortified by the audience reaction that he left the stage in the middle of a performance and dropped out of sight. Three years later he reemerged, and once more performed Mingfeng Ji(Legend of the Phoenix) at the same time as Li. This time, Ma’s performance was much stronger than Lils. Liwas full of admiration, and acknowledged Ma as his master. After the performance, Ma explained how his acting technique had improved so much. Hearing that the current prime minister was as treacherous as the character he was playing, he had gone to Beijing to work in his household. Every day he studied the prime minister’s every move, until finally he grasped the essence of his character. Lis performance relied solely on technique. But Ma drew from real life create and refine his art. Ma’s legacy was his real-ization that studying technique is not enough. By emulating the object to be portrayed, technique may be both enriched and improved.

Contemporary with Ma was Shang Xiaoling(dates of birth and death unknown),a female Kunqu per-former from Hangzhou known for her consummate artistry. She was most famous for her portrayal of Du Liniang in Mudanting (The Peony Pavilion). When Shang Xiaoling’s lover left her, she was grief-stricken and sank into a deep depression. One day, she was onstage performing the scene in which Du Liniang bitterly yearns for the perfect love. Suddenly overwhelmed with the pain of her own lost love, her face flooded with tears and she fell down dead on the stage. If it may be said that Ma drew inspi-ration for his acting from real life, then Shang Xiaoling truly became one with her character. Her own heartbreak became the psychological basis for her understanding of the story and her portrayal of her character. This identification was so powerful that it resulted in her final, stunning performance.

During the early years of the Qing Dynasty, the renowned Hanxiang Kunqu troupe of Suzhou was invited to give a performance at a private home. Unexpectedly, the performer playing the jing(paintedface) role was temporarily unable to perform. On the advice of a friend, the manager of the troupe in-vited Chen Mingzhi(dates of birth and death unknown),a member of a rural folk troupe, to fill the part.

Chen Mingzhi was a person of small stature with a very deep speaking voice. He appeared to be quiteunsuited to the jing (painted face) role, which requires bright, high-pitched singing and an imposing appearance. Furthermore, he was a total unknown. As a result, the members of the Hanxiang troupe greeted him with disdain and contempt. At Chen Mingzhi’s first performance, the audience requestec that the troupe perform Qianjin Ji(The War Between Chu and Han). The other troupe members knew that this work was the ultimate challenge for the jing (painted face) role, and were afraid that ChenMingzhi was not equal to the task. Chen Mingzhi, however, was not worried at all. Donning the general’s costume and thick soled boots, suddenly he was transformed into a tall and majestic figure. By the time he had finished applying his facial makeup, he had convinced everyone that he was Xiang Yu, the King of Chu. When he took to the stage, his regal bearing, martial arts skills, and acting techniquewere beyond belief. And when he opened his mouth to sing, his voice shook the dust off the rafters. The audience watched in silent amazement, afraid to make a sound until the performance was over. Only then did the hall erupt into cheers and applause. The other members of the troupe were thoroughly humbled and apologized to Chen Mingzhi for how they had treated him. They then sincerely invited him to join their troupe as a permanent member.

Shang Xiaoling’s story offers an example of the identification that can occur between performers and their characters. Chen Mingzhi’s story illuminates the difference that exists between performers andtheir characters. Sometimes, as in Chen Mingzhi’s case, they may even be total opposites. Kunqu artists enter the interior world and make it manifest. They must draw close to their characters in the depths of their hearts, while maintaining a certain distance from them in real life. This dichotomy informs every aspect of Kunqu performing.