Kunqu and Popular Culture

11 min readKunqu opera originated among the common people,and owed its wide appeal to the creative reformsof folk musicians such as Wei Liangfu.It may be said that from its very beginning,Kunqu was the product of popular culture.Over the course of its development,the writers and scholars of China’s cultural elite came to play a crucial role as well.But without the active participation of the common people,the newly mature Kunqu would never have spread throughout Chinese society as rapidly it did,let alone dominate the Chinese stage for such an extended period of time.As Kunqu opera becamein-creasingly widespread,it was influenced not only by Kunqu folk performers,but also by the demands of audiences composed primarily of farmers,merchants,and common townsfolk.As a result of this dynamic,Kunqu cast off many of the rules and restrictions of the cultural elite,emerging as a vibrant emissary of popular culture.

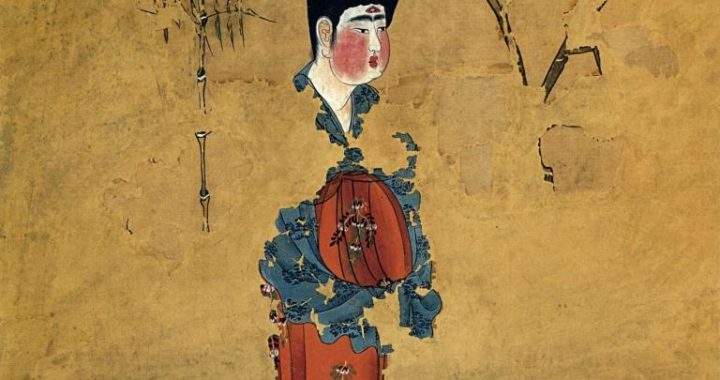

Zhao Wuniang in Kunqu opera Pipa Ji(The Story of the Pipa),by Tang Wenxuan(b.1925AD)The artistic status of Kunqu is quite similar to that of European opera. But in the West, it would behighly unlikely to find ironworkers or shopkeepers spending their spare time singing arias from The Marriage of Figaro by Mozart(1756-1791 AD) or La Traviata by Giuseppe Verdi(1813-1901AD). In China during the Ming-Qing period, however, everyone from butchers to farmers, regardless of their level of education, could sing famous Kunqu arias note for note. Many such examples may be found in the essays of the literati of the time. One concerns a butcher from Jiangyin, whose aged parents were very fond of drinking spirits. To express his filial piety, every day the butcher would bring his parents daily tipple back from the market and sing Kunqu arias for them as they drank their fill. This butcher also was known for getting roaring drunk with a group of beggar friends, singing Kunqu at the top of his lungs to his heart’s content. This type of situation was very common among the lower classes of the Ming-Qing period. During the Kangxi reign period(1662-1722 AD) of the Qing Dynasty, the Kunqu operas Qian Zhong Lu(The Slaughter of Thousands) by Li Yu and Changshengdian(The Palace of Eternity)by Hong Sheng were performed to wide popular acclaim. Two famous arias from these works became so widely known that they were the “pop hits”of the day. People from every walk of life were able to sing a few lines of these songs.

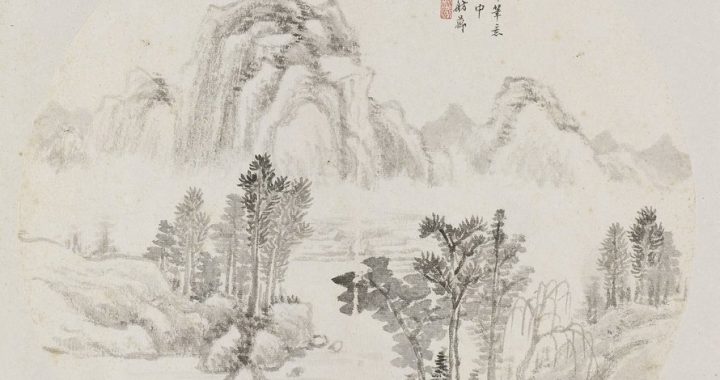

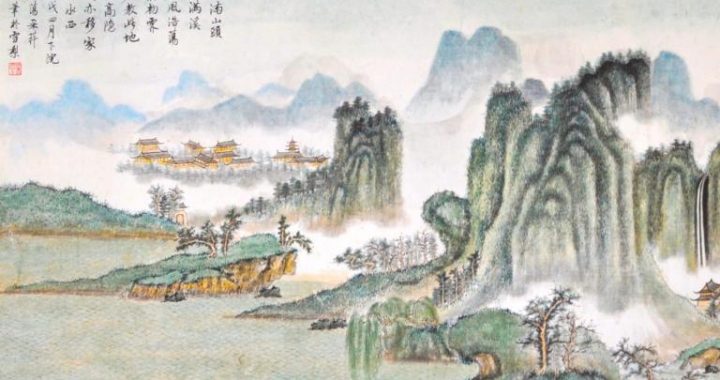

Huqiu Mountain, Suzhou

Among the most remarkable scenes of the Ming-Qing period were Suzhou’s great Kunqu gatherings.

Every year on the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar month, the entire population of Suzhou would travel to Huqiu Mountain, where they gathered under the brilliant full moon to engage in spontaneous per-formances of Kunqu opera. The slopes of the mountain were covered with people from every level of society who came for the event. Among the participants were city dwellers of every occupation, literati and local gentry, young women of the common people, courtesans and performers, servants of rich families, playboys and pleasure seekers. Even thieves and rascals would circulate through the crowd.

Everyone would bring a mat to sit on. As the moon started to rise, the sound of gongs and cymbalswould rise from hundreds of sites up and down the mountainside, blanketing everything in a thun-drous wave of sound. Around seven o’ clock, the percussion instruments would gradually cease, and people would start to sing Kunqu arias with the accompaniment of wind and string instruments. The brouhaha of people talking and debating the merit of the singers made it hard to clearly make out the lyrics or melodies.

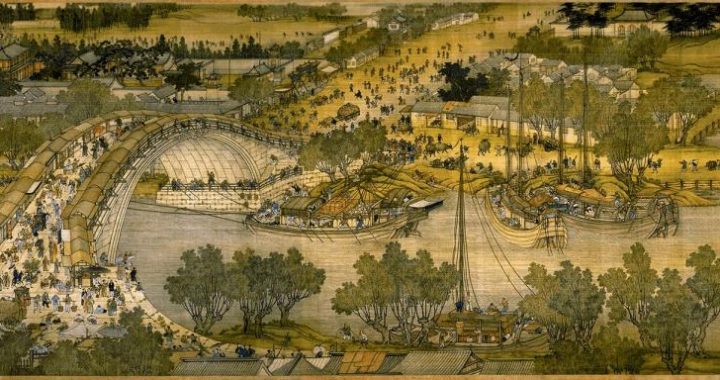

Rural theatrical performance;Qing Dynasty(1636-1911 AD)

As it got later,the surrounding audience would disperse somewhat,and people sitting on mats would start to sing one after another.After nine o’clock,the onlookers would quiet down even more,with the performers singing to the accompaniment of a single xiao(vertical bamboo flute).The combination of the low and resonant tone of the xiao with the melodious singing was nothing short of magical.By midnight,the mood would become so haunting that not even a mosquito would dare to disturb the remaining singers.At this point,a solitary person perched on a rock high up the mountainside would start to sing a cappella,relying entirely on purity of tone to captivate the listeners below.The singer’s voice would sometimes be as soft and gentle as a silken thread,and sometimes so loud and clear that it shook the heavens.Every syllable would be stretched out to create the maximum emotional effect.

The hundred or so listeners still remaining on the mountainside would enter the singer’s world body and soul,intently focusing on every detail of the singing to the exclusion of all else.The great majority of the people who attended the great Huqiu Mountain Kunqu gatherings were common townsfolk from Suzhou,for whom the yearly artistic exchange was nothing less than a ceremonial celebration of life.

Block print edition of Xilou Ji(The West Tower);

Qing Dynasty(1636-1911AD)

As the popularity of Kunqu opera spread throughout China during the Ming-Qing period,more and more Kunqu aficionados appeared among the lower strata of society.The demands of the common people on Kunqu performers were extremely high,sometimes even surpassing those of the gentry and literati.A story is told about a Kunqu dan(female role)performer in Suzhou who played the part of Zhao Wuniang,the heroine of Pipa Ji(The story of the Pipa).Once during the scene in which the impov-erished Zhao Wuniang sells her hair on the street,the performer’s sleeve accidently fell back,revealing that she was wearing a ring.The audience immediately started loudly debating how the character could be wearing a gold ring,since she had already sold all of her family’s possessions.The performer,becoming aware of the uproar, took off her ring and threw it into the audience, saying that it was only a worthless bronze trinket. If it had really been gold, she explained, the character could have sold it and wouldn’t have had to sell her hair. Only then did the audience quiet down. The common people were so familiar with the plots of Kunqu operas that not even the smallest detail escaped their notice. No one was more dedicated than these audiences, whose exacting attention embodied their passionate devo-tion to Kunqu.

The female performer who played Zhao Wuniang was not the only one to attach such importance to the opinions of the common people. Many famous Kunqu dramatists also jumped to their tune. Yuan Yuling(1592-1674 AD), famous for writing the Kunqu opera Xilou Ji(The West Tower), once attendeda banquet at a friend’s home. That evening, as he was riding home in a sedan chair, he passed the house of one of the gentry where the opera Qianjin Ji(The War Between Chu and Han) was being performed.

The sedan bearers, hearing the singing emanating from inside, exclaimed that on such a beautiful night, the performers should have been singing Yuan Yuling’s Xilou ji(The West Tower), rather than Qianjin Ji(The War Between Chu and Han). Yuan Yuling, whose dealings had always been with the literati and gentry, was amazed to encounter fans of his work among laborers of the lower classes. Learning that this opera, into which he had poured his heart and soul, was beloved among the common people, he was so excited that he almost fell out of his sedan chair. It can be seen from this story that even among Kunqu writers who regarded themselves as the most brilliant of the literati, earning the acclaim of the broad masses was considered an exceptional honor. This is because the common people always comprised the majority of Kunqu audiences.

Kunqu opera Baihua Zengjian

(The Princess Bestows a Sword), performance still

Universal education was an unknown concept in ancient China. The dissemination of knowledge re-lied for a large part on traveling theatrical troupes. Especially for rural people with no access to school-ing, Kunqu opera was the primary means through which they learned about history and philosophy.

In addition to providing artistic gratification, Kunqu instructed the rural population in traditional ethical concepts and the basics of Chinese history, and served to foster their interest in literature and art. It is told that during the final years of the Ming Dynasty, an illiterate woodcutter from Wu County in Suzhou went to see an outdoor Kunqu performance. When the corrupt official appeared onstage, the woodcutter flew into a rage and leapt up onto the stage, beating the performer until he was bloody.

Only the quick intervention of the onlookers saved the performer’s life. This hotheaded woodcutter had lost the ability to distinguish between theater and reality. But from another perspective, it can be seen that Kunqu opera was instrumental in forming his fundamental ethical belief system, and foster-ing his desire to support justice and oppose evil.

Merchants comprised one of the most unique segments of the lower classes of the Ming-Qing period.

According to the traditional Chinese social hierarchy of “scholar-farmer-artisan-merchant,”mer-chants theoretically occupied the lowest rung of society. In actuality, the rapid economic growth of China’s southeastern region during the Ming-Qing period led to the concentration of large amounts of capital in the hands of the merchant class, and a resultant rise in their social standing. An organic rela-tionship existed between the dynamic merchants of China’s burgeoning cities and the newly emerging urban culture. These merchants made exceptional contributions to Kunqu opera during the Ming-Qing period.

Zhong Kui in Kunqu opera Zhong Kui Jia Mei

(The Marriage of Zhong Kui’s Sister)

The participation of merchants in Kunqu opera was a gradually evolving process. At first, merchants regarded Kunqu solely as entertainment,a way to relax and unwind from the daily grind of doing business. But before long, they realized that Kunqu performances offered an excellent venue for social interaction, ideal for ingratiating themselves with imperial bureaucrats, seeking the support of influ-ential clients, and furthering their commercial pursuits. Later, investing in Kunqu productions also became a means to display their power and enhance their social status. Under these circumstances, merchants became influential supporters and participants in Kunqu opera. During the Qianlong reign period(1736-1795AD),a large group of merchants were active in Suzhou. These merchants held dozens of banquets at various Kunqu venues every day as part of their commercial activities. Tensof thousands of local people made their livings from these Kunqu events. Yangzhou,a center of the salt trade, was an even more important Kunqu region. Rich merchants established numerous private Kunqu troupes in order to flaunt their wealth. These merchants were known to spend upwards of

10,000liang of silver on costumes of a supporting role in one of their private Kunqu productions. The stage sets were also extremely opulent. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the merchant class provided the primary backing for Kunqu opera during the mid-Qing Dynasty.

The Qing Dynasty saw the popularization of Kunqu opera throughout China. Kunqu troupes were active everywhere, from the north to the south. Thanks to its huge popularity, Kunqu came into ex-

tensive contact with the common people of China’s lower classes. Kunqu troupes actively incorporated local folk culture wherever they performed, in order to better accommodate the artistic preferences of the farmers, merchants, and townsfolk who made up the bulk of their audiences. As a result, popular attitudes and thinking came to pervade Kunqu productions, quietly transforming its appearance and expression. After the mid-Qing Dynasty, Kunqu performances came to consist primarily of selected scenes of traditional operas. Kunqu folk troupes skillfully maintained the plot, structure, and lyrics of the original works, while also incorporating aspects of popular and urban culture into their perfor-

mances. By increasing the humorous lines of the jing(painted face) role and the chou (comedic) role and stepping up the onstage action, they brought new energy and vitality to the Kunqu stage. At the same time, they created a body of exciting martial arts skits that appealed to the tastes of popular audi-

ences. In this way, Kunqu opera, originally an embodiment of the culture of the literati gradually came to embrace popular culture and draw nearer to the common people.

An example is Mudanting(The Peony Pavilion). In the original version, there is a scene in which Du Liniang dreams that she has a tryst with Liu Mengmei, and a flower spirit gives them flowers. But this scene was extensively revised by Kunqu folk troupes. They added a deity in charge of sleep and dreams, who magically draws Du Liniang and Liu Mengmei into the dream world. Twelve flower spirits then appear on stage, one for each month of the year. The singing and dancing of the chorus of flower spirits

creates a lively and romantic atmosphere, totally different from the serious mood of the original opera.

The revised version was enthusiastically received by popular audiences throughout China.

The polytheism of popular Chinese culture was clearly reflected in Kunqu opera. The common people of ancient China put great value on the quality of real life. Their spiritual beliefs were correspond-ingly pragmatic. Any deity that could benefit them in real life, or at the very least not harm or imped them, was considered worthy of their veneration. During the Ming-Qing period, many folk Kunqu performances were held in honor of various deities. Among the figures worshipped in ancient China were deities that embodied Nature and Humanity, as well as spirits, ghosts, and immortals possessing supernatural powers. The Chinese pantheon also included ancestors and historical figures who had been deified. These figures all have their place in the Kunqu canon. Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, is a representative animal spirit. Rulai Fo(Sakyamuni Buddha) is a Buddhist deity; Yu Di(the Jade Emperor), Si Da Tian Wang(the Four Great Heavenly Kings), and Taishang Laojun are Taoist deities. Er-shiba Xiu(the Twenty-Eight Constellations) represent various human and Nature deities. Zhong Kui is a historical figure who was an upright scholar while he was alive. After he died, he became a guardian spirit responsible for vanquishing demons, widely revered by the Chinese people. In a scene from the Kunqu opera Zhong Kui Jia Mei(The Marriage of Zhong Kui’s Sister),a group of ghosts carrying a single lantern and a broken umbrella, cluster around Zhong Kui as he hurries down the road, his traditional talisman against evil spirits. This unforgettable scene graphically illustrates the veneration in which the Chinese people held Zhong Kui.

The influence of polytheism on Kunqu opera is even more apparent in the structure and content of the traditional operas. Many works reflect the unspoken belief in multiple deities and karma, using the stage as a means to transmit these concepts to the masses. The Kunqu hero, encountering dange often is rescued by spirits or extraordinary figures sent by spirits. Even if the hero temporarily meets with failure or death, supernatural assistance always ultimately results in victory or rebirth anda happy ending.

Kunqu opera entered a period of decline after the mid-Qing Dynasty. However, thanks to an infusion of vitality from the common people, it was able to survive and coexist with various regional operas. From this it can be seen that Kunqu was not solely the embodiment of elite culture, or merely the product of popular and urban culture. Containing elements of both classical elegance and common customs, Kunqu opera blended palace culture, the culture of the literati, popular and urban culture to create a cultural phenomenon unique in traditional Chinese arts.