A Home in Southern China

14 min readSome cultural rites are celebrated throughout modern China. Grave Sweeping Day, the poetry of Xu Zhimo, the twenty-four divisions of the lunar calendar, the eight Chinese cuisines, emperors’ names and their dynasties, the nineteenth-century humiliations of China by Europeans, the rituals of theChinese New Year and also many colloquial sayings. One of those sayings runs: Above there is Heaven, below there is Sushou and Hangshou. Between those two cities— the former in south Jiangsu and the latter in north Zhejiang -lies the town of Wuzhen. This exact area, with Wuzhen almost at its centre, was known once as the state of Yue and later as Wuyue. It was in those ancient times a rich independent country. Its last period of independence was in the tenth century when it was prosperous, culturally different and vital. However, it lackedthe military resource to remain independent. Wuyue was absorbed into the Northern Song dynasty. It never re-emerged as a politically independent entity.

The southern part of Jiangsu and the northern part of Zhejiang are known for more than their natural and, through their gardens, man-made beauty. Its fertile soil and abundant water also encourage the farming of fish, silk, tea, rice and the production of rice wine. So blessed indeed that the English phrase which springs to mind is ‘ God’s Own Country’. The Chinese use a number of idioms to describe this area. One is Yanbou Yaosai, suggesting these provinces are the throat of the country’ and therefore crucial to China, both emotionally and practically. Another refers to it as the Kingdom’s stomach and heart’, Sanwu Fuxin.

Hangghou then was known as Xingeai, literally translated as the Temporary Capital of the Southern Song’, which Marco Polo visited in the late 1200s at the beginning of the Yuan dynasty. It was temporary’ because the Jurchen invaders had displaced the Northern Song from Kaifeng and the reluctantly named Southern Song deluded themselves into thinking that they would return north.

Marco Polo referred to the city of Hangzhou as the finest and noblest city in the world. Other epithets for this area have been Yumi Zhi Xiang, the land of fish and rice, and Sichou Zhi Fu, the mansion of silk. That this one stretch of land should have so many flattering sobriquets is telling. The Chinese themselves, as well as Europeans, are impresed by these lands. They became synonymous with luxury and, most importantly, high cultural achievement.

Wuzhen is found at 30 degrees north and 120 degrees east, or in layman’s terms half way down the eastern coastline of China and a little inland. It is only five metres above sea level. The land in the immediate vicinity is flat. Historic Hangzhou, the provincial capital, lies southwest of Wuzhen eighty kilometres distant. Mighty Shanghai dominates the mouth of the Yangtze River 132 kilometres northeast. Beautiful Suzhou is ninety kilometres due north. Little Wuzhen is a town built between numerous little waterways which has never nurtured more than 50,000 souls but is surrounded by larger family members of this ‘ Paradise on Earth’.

This praise about the land surrounding Wuzhen is repeated throughout China, both in past and present times. Some emperors, such as Qianlong in the eighteenth century, were thought to have ordered repairs to the Grand Canal in order that they could travel from the north to visit these places of such reputed beauty. Modern Chinese instantly recognise the name of Wuzhen and, if they have not yet visited the town, mention in the same wistful manner many declare their wish to see Cambridge in England, that they intend to visit one day soon.

Northern China is not without its natural beauty; the mountains and coastal land of Shandong province to the south of Beijing is the match of any Chinese landscape elsewhere. The austere plains of the Dongbei in the very northeast have a distinct beauty, as no less do the plains of Mongolia and the mountains of Tibet or Yunnan, the latter having the most diverse landscape ofany Chinese province. There is immense physical beauty everywhere to be found in China. However, in the historic consciousness of the Chinese it has long been the northeastern and southeastern coastal parts of China which counted most. Government bureaucrats, fierce soldiers and the ruling class came out of the north. Culture, businessmen and beauty were the preserve of the south. It was also the south which fed its water up to the arid north. So too the south, and particularly the provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang, sent its rice northwards.

This fertile southern land has nursed a rich culture. In the battle for Beauty Honours’ between northern and southern China, there is no contest. Wuzhen, Suzhou and Hangzhou triumph, but their triumph may also have had much to do with a psychological dominance. The south, and Wuzhen, has always been richer, produced more artists and has been the home of some of China’s most outstanding dynasties; though China has been ruled mostly from the north, the awe in which Wuzhen, Hangzhou and Suzhou are held might also just have a little to do with a northern sense of cultural inferiority.

The landscape near Wuzhen is spectacular. There are beautiful mountains, such as are captured in the native’ or guobua style of Chinese painting. The vertiginous painted mountains of the Song dynasty artist Guo Xi are typical of this style. Landscape painting in China was the most highly reputed of all Chinese painting genres. The mountains near Wuzhen are widely admired.

Capturing this beauty and spreading knowledge of it through China contributed to the region’s reputation. Landscaping artists who painted around Wuzhen practised the most respected genre of Chinese art. In the West, by way of contrast, landscape art was considered the least reputable. This English prejudice caused the outstanding landscape artist John Constable to be denied the hand of Maria Bicknell for many years. His rich putative father-in-law was prejudiced against landscape painting. He feared such employment could not possibly support his daughter in a style suiting her social position.A Chinese painter of such focused brilliance as Constable would have been more easily married in China.

There is also abundant water near Hangzhou. From the vast Yangtze River, to the large West Lake of Hangzhou, and the Grand Canal through to the small streams which thread through Wuzhen, there is water everywhere. Mountains reaching down to water, as in Scotland and Switzerland, are usually thought very attractive. Such is the case with Wuzhen. The climate is also pleasant; it has warm weather, even if it is often a little humid, with 1,800 hours annual sunlight. Comparatively in Europe, Malta at 3,000 hours has the most sun; Eastbourne, England’s sunniest spot has 1,900. January is Wuzhen’s coldest month with average temperatures around 1℃, July the hottest with an average of 28℃. Wuzhen enjoys four distinct seasons, which have proved important for its production of both rice and silk. Mulberry trees, whose leaves feed thesilk worm, grow easily, as do Ginkgo bilobas and the maidenhair tree. There is a mixture of other evergreen and deciduous trees. Azaleas are plentiful, evidently easily extracting the acidity they need from the dark rich earth of this region.

One author nurtured in Wuzhen, Mu Xin, in the 1980s wrote of picking the azaleas flowers to ‘ suck out its honey-tasting pollen’. Roses too grow willingly.A Westerner recognises much of the flora.

During the 2015 G20 meeting,’ Paradise on Earth’ was the phrase used to announce the next meeting would be hosted in Hangzhou. The city was spruced up in the manner after which the English Queen must think the entire country smells of fresh paint. Manufacturing businesses were closed to dent pollution, migrant workers went home, driving was restricted, and some people were encouraged to leave on holiday, while other locals were greatly inconvenienced by the requirements of modern security. Hangzhou folk were even encouraged to fight flies, cockroaches, mosquitoes and rats’. Ever a civilisation to latch onto numbers to carry a message, in the way of Mao’s ‘ Four Olds’ or ‘ Five Black Categories, the exhortation in 2016 was to deal with ‘ The Four Pests’.

The make-over of Hangzhou extended to Wuzhen, which town delegates and journalists were encouraged to visit.

The re-crafting of Wuzhen had started seventeen years earlier, in 1999; estimates of the restoration cost range from £200 million to £400 million. The variance merely confirms accountancy as a form of art rather than a science.

Whatever the figure might be, what matters is that a mighty investment over twenty years has rescued this town from terminal decline and oblivion.

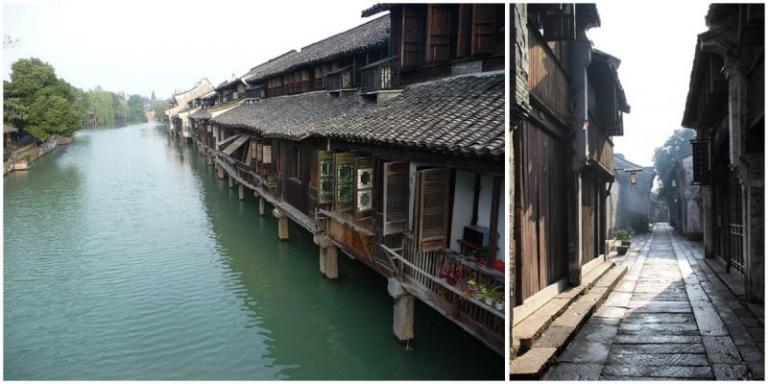

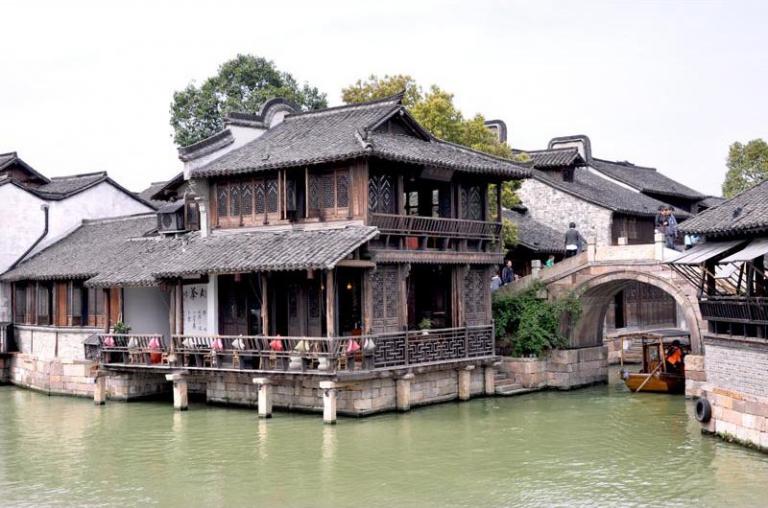

The money has been spent with great care and sensitivity. Moving around Cambridge, England, there are stretches of fifteenth-century college walls, of Queens’ College for example, which stand more or less as they were constructed 600 years ago; but only ‘ more or less, because, on occasion,a few metres abovethe ground an area of red bricks from the 1960s on top of some that are 500 years older can be noticed by the sharp-eyed observer. Wuzhen seems free of such calumnies. Only original materials, or at least if they are new they are totally equivalent to the old, have been used. Even at night the Chinese devotion to often excessive multi-coloured neon lighting has been tamed. Waterways, the eaves of the wooden homes and bridges have certainly been lit, but only with subdued off-white lighting.

In 2016, more than 7.5 million visitors squeezed down its delightfulgranite-surfaced alleyways and crossed the numerous hump-back stone bridges above the clear waterways. The wooden homes with tiled roofs have different shapes and sizes. As with most public areas of China, the town is kept immaculately clean by an army of elderly street-sweepers. Pensions may be beneath modest levels by Western standards for most people in China, but the encouragement of younger pensioners to take up such employment surely has a financial advantage as well as an obvious health benefit. The Western streetsweeper is usually half the age of the Chinese sweeper, and, it would appear to the casual observer, often less happy.

After the water, and the wooden homes built alongside the small canals, it is stone that makes the next impression. In the centre of town there is little to be seen of the famous dark fertile soil which once brought wealth to its inhabitants.

Every alleyway and small square is paved with irregular deep-cut granite paving stones. Occasional patches of earth provide sustenance to the few trees whichremain but there are not many of them. The emphasis in this town is on water, as a means of travel,a means of cultivating rice in the fields and as a source of fish. The alleyways are narrow and would never have accommodated even the earliest cars, let alone their broader modern descendants. The peace of ambling visitors is only disturbed by scooters delivering provisions for shops or the inns.

Those paths nearest the main waterway are straight, others bend and weave due to some long-forgotten reason.

The water in Wuzhen is both a source of beauty and a reminder of its power to support a community through trade. It shares in fact characteristics with a town like Cambridge, England. It too is small, even if it carries more cultural weight. As the River Cam dominates Cambridge, and was the first source of community wealth, so it provoked the building of many bridges. So too is Wuzhen, which still has almost forty bridges. Its waterways were, like the Cam and its tributaries, the arteries of the town; the water itself is calm unlike that of the streams in the nearby mountains. Those streams carry water down their steep inclines as if it were boiling. Wuzhen water is gentle. Wuzhen is peaceful.

This blessing of water extends to the neighbouring provinces. Many parts of China from ancient to modern times have suffered from periodic water shortage but Wuzhen has rarely been amongst them. It has suffered from flooding, but drought has not been one of its demons. Some of the region’s rivers are well known. The Xin’ an River is famous for its mist. The River Fuchun is esteemed for its elegant shape and tranquility. The Qiantang River or the Qian River, the largest in the province, is referred to as a historical scroll from which can be read history. Some people call it -half jokingly and half in admiration of the prosperity of the areas along the river -the ‘ Money River’: the Chinese character’ Qian’ also means money, although this’ Qian’ in reality derives from the family name of the Wuyue kings. There are main rivers and many subsidiaries which are recognised as the’ birth mothers’ of Zhejiang communities such as Wuzhen. There are other water towns such as Zhouzhuang, Xitang, Tongli, Luzhi and Nanxun. Each of these lies slightly to the north between Wuzhen and Suzhou. The life blood coursing through the arteries of Wuzhen is indeed its water. It has lived, prospered and suffered through its water.

In fact, this area of China, which comprises the provinces of Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Fujian, and Guangdong to the south, is dominated by water. Their mountains, lakes and streams receive the most precipitation of all areas in China. The average volume of rain in Zhejiang is over 1,000 ml per year, which compares to 796 ml in Liverpool, England and to Cambridge, England’s driest location,553 ml. Such amplitude has driven Zhejiang culture and its economy.

It has long provided the water-hungry crop of rice to much of the country and, since the issue of water shortage in the northeast was addressed in the 1950s, water as well. Through the South-North Water Transfer Project, water from the Yangtze River near to Wuzhen is now pumped north to reservoirs near Beijing.

In Chinese culture, water represents stillness and conservation. Both qualities apply to this part of modern China. Taoists associate water with intelligence and wisdom, adding that its character stretches to flexibility and pliancy. It brings good things, riches indeed, as the nickname for the Qian River, the’ Money River’, suggests. Guo Pu, the Chinese Immortal, would be content with such comparisons. Naturally water is part of the Chinese Five Elements’ Wu Xing’ philosophy, together with metal, wood, earth and fire. As water plays itspart in the ‘ enhancing cycle’ by nourishing wood, so it has sustained Wuzhen.

Lakes and rivers make up 6.4 per cent of Zhejiang province. In Britain,a place which is not exactly short of water the comparative percentage is 1.3. Evidently water flows around the lives of Wuzhen people as blood through their veins.

Mountains provide another feature of the land around Wuzhen. Roughly seventy per cent of the province is composed of mountains; the British comparative statistic is around fifteen per cent. Steeper than most in Britain, they reach into the soul of Chinese culture. Mountains are where the Heavenand Earth meet, where the Gods dwell and the Immortals interact, should they wish, with mere humans. Carved pieces of precious jade found in emperors’tombs of Han dynasty are shaped like mountains with vertiginous paths winding upwards which can lead humans to those encounters with the Immortals.

The dominance of mountains here and in many other areas of China must in part explain artists’ interest in their portrayal. It developed into an admired independent genre in Chinese painting from the time of the Han. As an ageing European might seek solace from his garden, preferring the company of his plants to those of his fellows, so the learned Chinese man preferred the permanence of their natural world which offered a valued sanctuary as one dynasty crumbled in chaos before the next was established.

Many artists, particularly during the Song dynasty, chose to live in seclusion on a mountain near Hangzhou. Their paintings depict mountains reaching down to water which have within them numerous folds to suggest their summitcan be reached by a wandering sage weary of the world. The painting includes many deciduous trees, pines presumably; some of those trees were devoured during the twentieth century but Zhejiang still has a forest coverage of sixty-one per cent. It is the flora of the region around Wuzhen that provides so much of the colloquial symbolism which appeals to the Chinese; the pine tree, for example, represents strength and perseverance with the ability to maintain one’s integrity regardless of the hard circumstances of a mountain side.

Paintings often include a pavilion within the folds of these mountains where the sage would ruminate alone. Indeed during the century of rule from 1271 by the Yuan invaders many educated Han Chinese were excluded from government service. The Southern Song literati from around Wuzhen and Hangzhou transformed their hilltop country estates into cultural retreats. Asa garden can be an extension of oneself, so too a painting of mountains could express the owner’s, and painter’s, values.

Of China’s own estimate of its ten most famous paintings, five are dominated by mountains; one is entitled Fuchun Shanju Tu or Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains by Huang Gongwang in the Yuan period; he too may have been excluded from office earlier in his life. The Fuchun Mountains are just to the southwest of Hangzhou in the Longmenshan range and the local river is named after the mountain. Half the long scroll -the other damaged section of the painting lies in Taipei -is held at the Zhejiang Provincial Museum in Hangzhou. Another of these ‘”Top Ten’ paintings is known as Qingming Shanghe Tu or Along the River during the Qingming Festiual by Zhang Zeduan in the early1100s. Critics dispute the exact translation of the painting’s title but it most likely carries the sub-title ‘ Peace and Order’. However, it indicates more thattrade is the outcome of peace and the captivating, bustling scenes packed with enchanting details of life seem more frenetic than peaceful. The river shown is the Bian River which runs through Kaifeng, the Northern Song capital a few hundred kilometres north of Wuzhen. The Bian is a broader river, the bridges mightier in consequence, than those of this southern water town but the scene could have been painted of Wuzhen. Another artist Lin Bu (also known as Lin Hejing) from the Northern Song period withdrew to Gushan Mountain, one of those painted by his predecessor, Zhang Zeduan. His love of plum blossom, one of the important winter flowers of this region, led him to write about flowers in his poetry.A line from his verse ‘ plum wife and crane son’ is still used as a metaphor for a lifestyle free of worldly concerns that can be found in this charmed area of China.

Water, the mountains, the forests of trees and spreading clumps of thick-stemmed swaying bamboo are the features of the lands around Wuzhen. These images make up what the modern Chinese, so many of whom are now squeezed into skyscraper apartments, still believe provide the essence of their culture.

Knowledge of that culture is not lost yet. Wuzhen was saved from terminal exhaustion and is reinforcing that knowledge. Before the restoration project, the town had been starved of oxygen, life-giving air sucked away by modern urbanlife. The town had been left behind. It is now transformed. Wuzhen is there to be visited, to be enjoyed and to buttress the cultural memory. For the moment, the east coast Chinese still have sufficient roots to return to the countryside for festivals such as those of the Chinese New Year and Qingming. Wuzhen celebrates a past culture which will maintain these cultural links. The stories of Wuzhen, and those of nearby Shaoxing, Suzhou and Hangzhou, carry a larger cultural footprint than might be expected for a simple water town in the Yangtze River delta. It is this footprint that is uncovered here.